Library Scavenger Hunt for Faculty Community-Based Learning Workshop

Today's post is by guest author Shauna Edson, Instructional Design Librarian at University of Wisconsin-Parkside.

Today's post is by guest author Shauna Edson, Instructional Design Librarian at University of Wisconsin-Parkside.

University of Wisconsin - Parkside Library has been participating in the Community Based Learning (CBL) summer workshop for faculty since 2016. Library staff are able to spend some face-to-face time with faculty, getting to know their course CBL project and connecting them with library resources. Beginning in 2019, the library created a scavenger hunt for the faculty to introduce new library resources, demonstrate active learning, and serve as an icebreaker for faculty and staff at the beginning of the workshop. The Library Scavenger Hunt forces faculty out of their comfort zone and introduces innovative library services, such as curriculum curation and instructional design (Edson, 2019; Edson, Antaramian, & Vang, 2021). The reflection discussion at the end of the game helps solidify many of the goals of community-based learning programs, including making creative connections and solving problems collaboratively.

Agree on Session Goals

Planning for the Library Scavenger Hunt began with establishing goals with the UWP Community-Based Learning department workshop organizers. We wanted participants to be exposed to community-based learning as well as information literacy goals, but we were also aware of needing to tie those together to create a cohesive experience. We also found out that the CBL workshop organizers wanted the Library Scavenger Hunt to serve as an icebreaker, pushing faculty outside of their comfort zone. This discomfort was a memorable experience to reflect on throughout the workshop and helped reinforce the service-learning goals, such as connecting with the community, collaborating for positive social change, and developing personal agency and critical reflection.

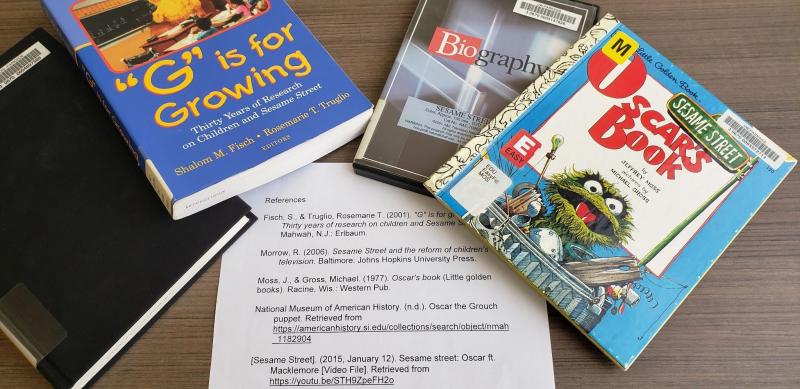

Another important goal was to take advantage of the research expertise that faculty already have and build connections to new library resources and services. I included traditional scholarly print materials as well as online digital media to emphasize the wide range of resources that can play a role in research instruction for community-based student projects. I also wanted to highlight the skills librarians have for curating curricular materials; the resources in the game are inspired by one service-learning project that showed a university collaborating with a local laundromat to incorporate storytime and tutoring services for the children who came to the laundromat with their parents (https://youtu.be/lvn38fS8l0A). I teased out different topical elements of the service-learning project, such as scholarly materials and children’s books.

Plan the Game

I had previously used a Breakout EDU box to design a scavenger hunt for other library programs, so I expanded upon that experience and created a custom game for the CBL workshop. In a previous article, I shared that “Breakout EDU boxes have been popular in K-12 classrooms in recent years because they offer a flexible active learning experience for a range of ages, number of participants and a diversity in abilities” (Edson, 2019, p. 31). Similar to popular escape room games, participants work together to solve clues and unlock number, letter, directional, and key locks. Instead of “escaping the room,” participants will break into a box which can be stuffed with whatever prizes you want. We usually include library swag since everyone loves free stuff, but for younger children we’ve included candy and other goodies! The game moves the instructor from expert to collaborator, an important mark of active learning design (García-Cabrero et al., 2018, p. 825).

Image 1: Breakout EDU boxes and locks

The Library Scavenger Hunt also included:

digital and physical clues to familiarize participants with service-learning and library resources.

websites, books, DVDs and CDs, computer, and projector.

6 Clues and 5 Locks (4 alphabetical and 1 numerical).

By appealing to the interests and experiences of participants, librarians can elicit more collaboration and participation. Therefore, clues were designed to relate to both service-learning and library resources. For example, one of our clues was a YouTube video about the laundromat storytime service-learning project. Since the library has a new Guttormsen Literacy Lab and a variety of new children’s books, I decided to include a few in Clue 6 to advertise those resources.

I provide these Library Scavenger Hunt Staff Instructions to the game facilitator which helps other library staff feel comfortable stepping in and helping. They basically have the answers to all of the clues and locks, just in case participants have questions or there are any technical issues.

Image 2: Books and references list for Clue 6. Participants find the References page and realize that several of the books & DVDs lying around the room are listed on the page. They have to see the pattern in the resources: Oscar the Grouch. This ties back to storytime and tutoring services shown in the service-learning YouTube video. The lock answer is O-S-C-A-R

Constructivist Learning Theory

Taking a constructivist learning theory approach to planning the Library Scavenger Hunt allowed us to consolidate our session goals in a memorable, fun, and interactive way. Constructivist Learning Theory sees learning as a dynamic process in which a learner constructs new ideas or concepts on their current/past knowledge and in response to the instructional situation (Gupta, 2011, p. 30). The instructor goes from Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side, encouraging students to take initiative and instructors to move to a facilitator role. The thing to remember with Constructivist Learning Theory is that learning is active rather than passive. Think: Movement, Conversation, Negotiation, Trying things, Failing, Noise, and a certain amount of Mess!

Here are five Constructivist Learning Techniques we used in our Library Scavenger Hunt to encourage active learning: Model, Scaffold, Coach, Explore, Reflect.

Model

Modelling is showing how experts perform a task. This gives participants a framework for their own activities and strategies (Collins, 2006, p.50). I usually start out the game by asking the group if they have ever done an escape room before. If someone has, great! I ask that they share out and give us tips, as the Library Scavenger Hunt will be very similar. They become the expert and I will sometimes encourage participants to go back to that individual and ask them questions. If no one has played an escape room before, I show an escape room youtube video so they get a sense of what to do.

Just as with library instruction, it is important not to assume that participants have a certain amount of prior knowledge. This is a game, after all, so we want participants to have fun. It’s important to spend that time in the beginning allowing them to learn from one another or from a YouTube video. It starts building the culture of collaboration among the participants and reinforces the facilitator role as collaborator, not teacher.

Scaffold

Scaffolding is designing effective tools and resources that guide learners and fade out assistance once learners show competence (Mayer, Moreno, Boire, & Vagge, 1999). On a very practical level, doing a practice run with staff prior to running a live game lowers the risk of mistakes and gives you instant feedback. You can easily see where to add more support and whether a clue can be streamlined. It’s great to be able to see how much time a game takes as well, since the CBL workshop is a busy multi-day event, and we need to be able to fit it into a certain time slot.

I’ve also learned to always share the Escape Room Tips poster before the game begins to help participants connect their previous experiences and skills with the game activities. Building that context can deepen the learning and build out more strategies for how to play the game.

Image 3: Escape Room Tips poster, (Rober, M., 2018)

The following 10 tips are listed in the Library Scavenger Hunt Staff Instructions and are discussed before participants begin the game.

- Think simple: Your clues are going to be things you and your students can check out from the library and/or use in your research assignments (websites, books, DVDs, and youtube videos). You will also use the computer and projector to figure out some digital clues.

- Search in obvious places: The clues are all on the tables. You aren’t going to find anything in the ceiling, in the computer, etc.

- Organize your items & clues: You will want to put clues together and see how they fit. Try things, make mistakes, and reorganize them.

- Focus on what’s stopping you. . .or don’t! Sometimes you’ll want to walk away from a clue and work on something else for a while.

- Assign team roles & communicate: This will be very fluid and casual. You won’t be assigned to groups but you will naturally work independently, in pairs, and in small groups. Then you will break apart and form new teams. Whatever works for you is allowed.

- Lock types: We have 5 locks in the room. Two of the locks are physical locks on a small and large box. The other three are paper locks taped to the desks to allow more social distancing!

- Code types: You’ll want to familiarize yourself with the types of locks so you know what kind of clues to look for. Some locks are numbers and some are letters.

- Written clues: A lot of the clues are paper print-outs, so make sure you read through them and use the computer and monitor if you need to! You may also have clues that lead to other clues and not directly to a lock code.

- Look for patterns: Put things together and see if you can see a pattern. Are several clues meant to work together to help you learn the code for a lock?

- Your host is your friend! Feel free to ask questions about the logistics of the game. Questions about the game content will be redirected to your teammates, but we can always help give small hints!

Another thing we tried this past summer is writing the locks up on the whiteboard and crossing them out each time participants opened one. It seemed to guide learners and motivate them towards their ultimate goal of cracking open the large Breakout EDU box.

Coach

Coaching goes hand-in-hand with teaching. Providing feedback, encouraging, listening, and prompting are just a few of the coaching behaviors educators do all the time (García-Cabrero, et al., 2018, p. 825). In playing the Library Scavenger Hunt, I’ve learned that some groups need more coaching than others. The poster is an important coaching tool. Rather than answering questions directly, the moderators can refer back to specific tips on the poster and coach the group towards or away from a particular outcome.

Usually, starting the game by sharing previous escape room experiences and the escape room poster tips is enough to get people into the game mindset. In my experience of hosting the game with different age groups, the younger and more cohesive the group, the less modeling and coaching a group needs. Some faculty have a harder time making the connection between active learning, research skills, and playing a scavenger hunt game. I’ve had groups that were hesitant to get started, so I will start out working side-by-side with them on the first clue. Solving the first clue is often all it takes to motivate and keep the momentum going. It is important to cheer them on when they figure something out on their own.

Explore

Exploring is when participants apply what they learn and pose and solve their own problems (Gupta, 2011, p. 43). This is where both moderators and participants need to be comfortable trying things out and maybe failing. Combining modelling, scaffolding, and coaching to provide a supportive exploratory culture should help encourage and reward risk-taking. It also helps to move chairs in the room away from the tables so that participants who are able can move around, pick up clues, and join group discussions as they explore.

Creativity and collaboration are two important skills to get participants exploring successfully. Creativity is “the ability to develop, choose, and integrate novel, unconventional, and innovative approaches” (Urbani, et al., 2017, p. 30). Collaboration is “the ability to work productively and equitably while valuing others in diverse educational settings” (Urbani, et al., 2017, p. 30). What’s great about creativity and collaboration is that they involve both active learning and making connections to higher level research skills that faculty already possess. So again, the Library Scavenger Hunt builds on the skills that participants already have to develop group cohesion and encourage exploration.

Reflect

Reflecting is when participants compare their understanding with others, which helps them verbalize their knowledge and thinking (Bada, 2015, p. 68). I or The Facilitator can encourage participants to reflect throughout the game by asking them to repeat something they said and asking others to listen or weigh in. Building in those small discussions will help participants remember, question, explore, and come up with new approaches to clues.

There is also reflection at the end of the Library Scavenger Hunt. The CBL workshop facilitators lead a discussion that helps tease out themes and make lasting connections for participants. It’s also important that the workshop activities model the way a CBL course will be structured, so faculty will be comfortable incorporating reflection discussions in the classroom. Some of the suggested reflection questions included:

- How did it feel when it was messy and you felt like you were failing (not getting the right clues)?

- How did it feel when you got a clue figured out?

- Think about the different resources in each of the clues. Why did we include each of those? Why were they important?

- How might some of these activities look in the CBL classroom?

- How might we have supported you more when you were playing the game?

Conclusion

One of the biggest benefits to designing this Library Scavenger Hunt is having the framework and experience for hosting a fun, engaging program that is highly customizable for different types of participants. We’ve hosted this game both online and in-person, with faculty, community members, and K-12 students. It can be as informal or as structured as you want. It really just depends on your goals! When I first suggested the game for the CBL workshop, I was intentional about planning and setting goals but also flexible as to the role it might serve and the long-term takeaways. This turned out to be a great approach, since the Library Scavenger Hunt is now a touchstone piece of the annual CBL Summer Workshop!

I can make a few recommendations to avoid making the same mistakes we made. I would definitely recommend having library staff help out as moderators and doing a run through together. Make sure you create a supportive, fun atmosphere, and bring in staff who are flexible and comfortable with messiness. One year, we also did an experiment that had mediocre results. We decided to throw the CBL Workshop participants into the game with little instruction and little coaching. After a few minutes, we stopped them to have a reflection on how they felt and where they were at in playing the game. We wanted to simulate how frustrating a CBL project can be and have them try to empathize with how their students might feel in that messiness. After that, we provided more instruction and hands-on coaching and their experience improved. While I think it was a memorable experience for the participants, I also hesitate to deliberately create frustration and bad feelings, even if we can turn it around and create something positive in the end.

In terms of higher-level information literacy goals, I would like to incorporate “Authority” more in future games because students need to understand that there are different types of expertise. The non-profit staff who partner with our CBL programs are experts on their own experiences. However, faculty are also experts because they study those experiences, gather data, and publish scholarly materials. Will the clients’ experiences show up in the scholarly materials? Why or why not? Students will need some help understanding how anecdotes are different from evidence but that the clients’ voices and experiences are still important and valid.

The most recent CBL Summer Workshop took place in May 2021. Faculty reported positive experiences with the game and were very engaged and motivated throughout. It may be a product of being away from one another for a year of COVID social distancing, but it seemed that this group was very willing to get their hands dirty, make mistakes, learn, and build something together. Just as in library instruction, however, the group cohesion and culture can make or break a game experience.

I’ve learned that incorporating just a few Constructivist Learning Theory techniques can activate learning and create a memorable experience for faculty during the CBL Summer Workshop. It would be great to help faculty extend that active learning into the CBL classroom. In the future, I would consider summarizing my own Constructivist Learning strategies and providing one-on-one consultations to faculty on CBL research activities or classroom icebreakers. That way, faculty interested in learning more will be able to plan out an activity, provide effective coaching, and incorporate a reflection piece.

References

- Bada, S. O. (2015). Constructivism learning theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 5(6), 66-70. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1c75/083a05630a663371136310a30060a2afe4b1.pdf

- Collins, A. (2006). Cognitive apprenticeship. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 47–60). Cambridge University Press.

- Edson, S. (2019). Escape rooms build better researchers. Codex: the Journal of the Louisiana Chapter of the ACRL, 5(3). http://journal.acrlla.org/index.php/codex/article/view/162

- Edson, S., Antaramian, E., & Vang, X. (2021, March 25). Break out of your K-12 outreach routine [Conference presentation]. Wisconsin Association of Academic Libraries Conference.

- García-Cabrero, B., Hoover, M. L., Lajoie, S. P., Andrade-Santoyo, N. L., Quevedo-Rodríguez, L. M., & Wong, J. (2018). Design of a learning-centered online environment: A cognitive apprenticeship approach. Educational Technology Research & Development, 66(3), 813–835.

- Gupta, S. (2011). Constructivism as a paradigm for teaching and learning. International Journal of Physical and Social Sciences, 1(1), 23-47. https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/IJPSS_SEPTEMBER/IJMRA-PSS374.pdf

- Mayer, R. E., Moreno, R., Boire, M., & Vagge, S. (1999). Maximizing constructivist learning from multimedia communications by minimizing cognitive load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(4), 638–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.4.638

- Rober, M. (2018). Beat any escape room: 10 proven tricks and tips. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwgaTYOx0RI

- Urbani, J. M., Roshandel, S., Michaels, R., & Truesdell, E. (2017). Developing and modeling 21st-century skills with preservice teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(4), 27–50.

All Service-Learning Articles by Month

- October 2023 (1)

- May 2023 (1)

- March 2023 (1)

- June 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- March 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (2)

- October 2021 (1)

- September 2021 (1)

- August 2021 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- January 2018 (2)

- November 2017 (1)

- September 2016 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (1)

- October 2013 (3)

- August 2013 (1)

- April 2013 (3)

- March 2013 (4)

- February 2013 (1)

- January 2013 (1)

- October 2012 (4)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (2)

- July 2012 (3)

- June 2012 (3)

- May 2012 (4)

- April 2012 (3)

- March 2012 (9)

- February 2012 (4)

- January 2012 (7)

- December 2011 (3)

- November 2011 (8)

- October 2011 (6)

- September 2011 (9)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (6)

- June 2011 (8)

- May 2011 (8)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (8)

- February 2011 (5)

- January 2011 (5)

- December 2010 (3)